John Bradburne - A Magnificent Life

John Randal Bradburne was born in 1921, the son of a parson who ministered to the Anglican community in the Cumbrian village of Skirwith, near Penrith. Two of his cousins were to become famous, the playwright Terence Rattigan and Christopher Soames, the last governor of Rhodesia.

After a spell in Cumbria John's father, the Reverend Thomas William Bradburne, took a living in Norfolk and the total of his offspring rose to five - besides John there were two other boys and two girls. John as educated at Greshams School in Norfolk. A wealthy Patron helped his family to send the children to good schools.

When was broke out in 1939 John joined the Indian Army. Considering his background and education, also the fact that his mother was born in Lucknow, India, he was an obvious candidate for a commission. On arrival in Bombay he was posted to the 2/9th Gurkha Regiment. Whatever John experienced in life was fodder for a poem and India was no exception:

Sacred bulls of lumb'ring size,

mooching 'mongst the stalls;

varied smells of merchandise

this Englishman enthralls

Shelves of food with flies a swarm,

betel nut and dust;

heavy air and very warm

but stay to look I must

Tongas reeling through the crowd,

(scarecrow ponies' task);

cripples, outcasts, beggars bowed;

old India's lifted mask

Holy men in wailing trance,

wand'ring on the road;

money lenders seizing chance

and counting all they owed

Idler babus drinking tea,

babbling empty news;

'British not worth ek rupee

their Naukri we refuse!'

Pie-dogs slinking in and out

(trapper, shops and feet)

feasts of garbage strewn about

each fly-infested street

Haughty camels: caravan

bearing bales of straw;

swearing, grumbling driver-man

here's nature in the raw!

There can be little doubt that John's days in India inspired him with a love for the poor and downtrodden. To a man of his upbringing it must have been a culture shock indeed. Little did he realise then that almost 30 years later he would be caring for lepers; even so the seed had been sown.

In 1941 John's brigade was posted to Malaya and John was to become something of a reluctant hero. When Pearl Harbour was attacked on December 7, 1941, the Japanese began their invasion of Malaya at Koto Bharu. Winston Churchill promised the full backing of the fleet to the troops trying to defend the Malay peninsula, but the sinking of the battleships Repulse and Prince of Wales was a severe blow. Consequently the men of the Ghurka battalion were told to pair off and to avoid capture. An amazing adventure then began for John and his comrade, an ex-Assam tea planter.

They lived off the jungle, escaping the clutches of wild animals, eating roots and wild berries as they headed for the coast. Here they captured a sampan and set off for Sumatra only to be shipwrecked and washed ashore. After a few days they captured another sampan complete with Malayan crew, and forced them to sail the craft to Sumatra.

Suffering from Malaria and heat stroke, John was carried aboard the very last British destroyer out of Sumatra. This vessel took them to a British cruiser, which ferried them to Bombay. After rest and hospital treatment, John went to Dehra Dun to rejoin the Gurkha regiment. It was there he met Father John Dove S.J., still a layman at that point. They were to be close friends until the day John died.

In 1943 he was offered the post of adjutant to the 5/9th Gurkhas. But John had no such ambitions and was content to remain with a mortar platoon. He now had time to apply himself to his three favourite pastimes - bird-watching, singing psalms and tending to the wounded. It was then he met Major General Orde Wingate.

Wingate was a distinguished jungle fighter. In the early days of 1944 the Japanese were preparing to attack Imphal, known as the 'gateway to India'.

Wingate's men became known as the Chindits and the plan was to drop behind the enemy to cut off their supply routes. A large force landed in Burma where John spent a whole year with the Chindits. Even in the heat of battle John's eccentricity revealed itself when he still delighted in bird-watching. At other times he sang psalms with the war raging all around him. Eventually John's recurrent bouts of Malaria forced him to be flown to Poona for hospitalisation.

Then it was back to England. Father Dove in his wonderful book Strange Vagabond of God described him as a hero and a misfit when he was in the army. This description aptly fits his life until the day he died.

Civilian life

John's search for God now began in earnest. Just as God acts in mysterious ways the paths to reach him can be bedevilled with snags and obstacles about which we have no conception; the twists and turns of fate leading us up seemingly blind alleys one day, and along joyful avenues of hope the next, frustrating us as we lose our way only to find the true path at last. John's path to God was very much as hit and miss affair.

He was a heather seed willing to be blown here and there by the whim of a mountain breeze, often trusting his fate to the toss of a coin.

A few words on eccentrics

Upon demobilisation John was issued with the statutory de-mob suit, raincoat and hat. One wonders if he ever wore them, or, if he did, was he comfortable in them? Convention was never his mode of life, there is little doubt that he was far happier in a forester's apparel - roll neck sweater, breeches and boots - when he took his first job for the Forestry Commission on the Quantocks in Somerset.

Here he was free to enjoy the celebrated Somerset cider in the forestry cab and local pubs, no doubt scribbling snatches of poetry on the backs of beer mats, verse notable for its praise of God and his wonderful gifts. He longed to serve this bountiful creator to the best of his ability, but how to do it eluded him.

He exuded love, and he was his own man and like most eccentrics he had his critics - 'crazy poet', 'upper class tramp', could well have been the thought in many people's minds who didn't understand him.

The nine to five regimented conventionalists can never come to terms with behaviour that is bizarre and bohemian. John was both to a degree!

A jovial monk am I

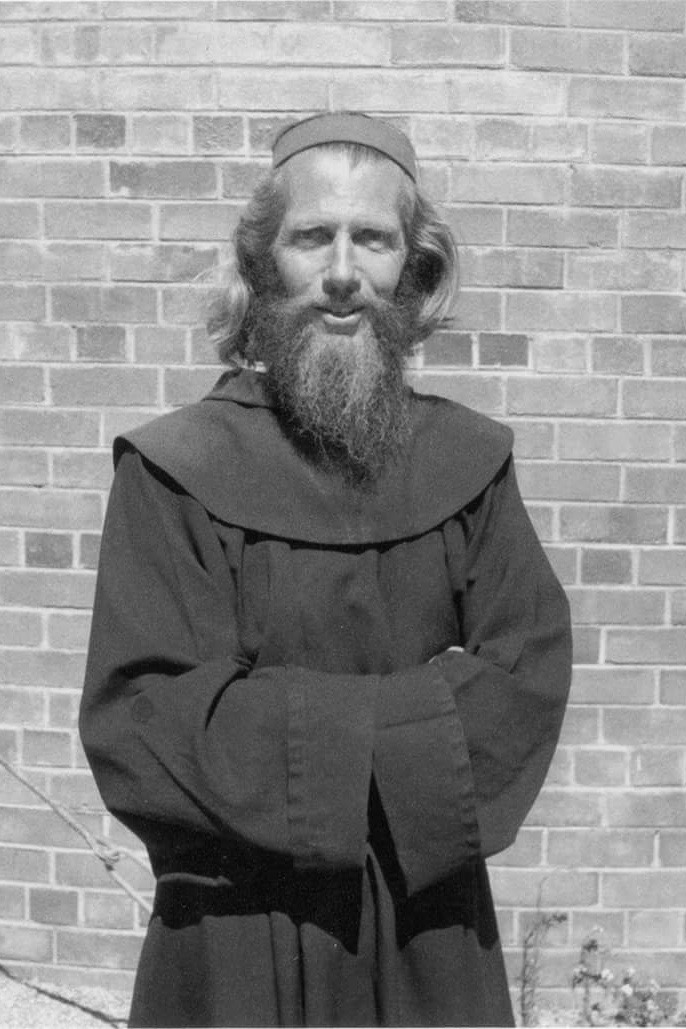

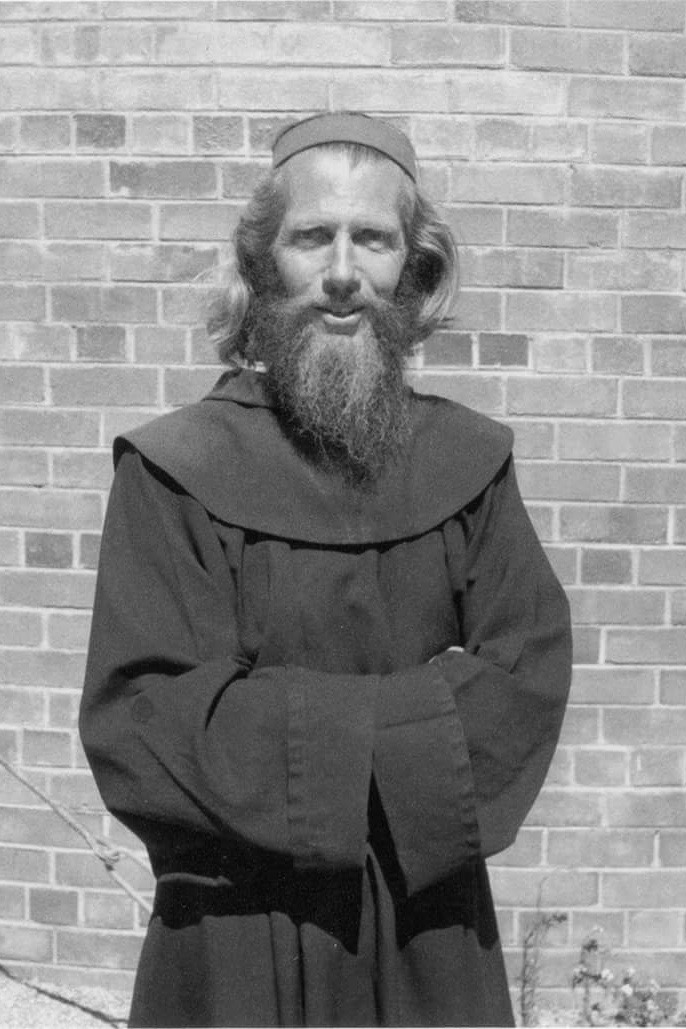

John's thoughts now turned towards the monastic life.

He was accepted by Buckfast Abbey and given employment as a gardener, a task he enjoyed, while he was being prepared for reception into the Catholic Church.

This took place in 1947 on the Feast of Christ the King. It was at this famous abbey that he first became interested in bees, which were to play a prominent part in his future life, even becoming recognised as a significant sign of his intercession after death.

"In a pub I was told a message had come, marked urgent! From all abbey bees...

'Twas as follows: 'Dear bard tho' we sing not but hum,

our life is not given to ease,

if you look in the sanctuary, you will observe there burns near the altar a flame:

'Tis fed by a pillar of flowers and herbs -

a wax candle - our title to fame!

To us, let he would think bees wanting in praise,

the lord gives this work as a sign,

and while others sing canticles marking the phase,

we cause his memorial to shine"

The Abbot did not feel he had a vocation for the Benedictine life. However, he agreed to him becoming a postulant but the rule for converts to the Catholic faith stated that he had to wait for two years before entering religious life.

John was bitterly disappointed. How was he to fill in two years?

Love lies in wait

John headed for Exmouth in Devon, and at Gaveney House he was accepted as a prep school master. John was so full of affection for everyone that it is surely not unusual that he fell in love.

The lady was much older but it made no difference, he was smitten. He was also torn in two. This was definitely not part of his plans or his dreams.

He couldn't help his natural instincts, yet it was the last thing he had bargained for.

It was back to Lady Luck again - the spin of a coin! Heads to remain, tails to leave the school.

It was tails - so he did a moonlight flit!

Buckfast Abbey got to know and disapproved and decided he could no longer be accepted as a postulant.

He knew deep down that he had a vocation - but for what?

Go to sea young man

John Bradburne was one of the most likeable of men, sincerity shone from every pore, those who knew him well grew to love him, yet there were those who could never understand him and even found his mode of life irritating. In a word, he was different. Would he ever settle into the normal stream of life? The advice from the abbey was to go to sea. John was advised to seek a life on the ocean wave 'to sort himself out'.

So he took a job on a fishing boat, a tough, rough life with little comfort and fraught with great danger. By the end of two voyages the salt air and the freezing conditions hadn't blown away his ambitions for the life of the cloister. Once he had regained his land legs he was knocking on the door of a Carthusian monastery, Parkminster in Sussex.

This order was formed by Saint Bruno in the 11th century. It was a contemplative order. He acted as a doorkeeper and working guest with the monks singing matins and lauds in the middle of the night and early morning.

Even the extreme cold of an unheated abbey in the depths of winter didn't deter him.

Rome

When the chance came to go to Rome on an all-expenses paid pilgrimage, John seized the opportunity. From Rome he planned to travel as a pilgrim, throwing himself on the generosity of others and the grace of God to see him through, convinced that his vocation in life was to convert the Jews to Christianity.

So off he set from the ancient city. John only had a recorded which he played at wayside stops, a penniless gentleman of the road, tramping the highway singing hymns to his own accompaniment and praying the office of Saint Francis of Assisi (he was by the time a member of the third order of Saint Francis) and singing the little office of Our Lady daily in Latin. Often in the company of ne'er-do-wells and beggars, he felt at one with Saint Francis. He was happy. At one with the poor.

In some ways St Francis and John had many things in common. Francis was the favourite son of wealthy Assisi businessman, Peter Bernadone, and in his formative years had a very comfortable home life. John Bradburne's father was an Anglican parson in a Cumbrian village when John was born.

But the family had aristocratic origins traceable to Godard Bradburne of Bradburne Manor, Derbyshire, who was born in 1199 and received a grant of the manor from Geoffrey de Cannies in the reign of King John. The family had its own coat of arms and John Bradburne of Hough became Lord of the Manor. His tomb is in the Boothby chapel of St Oswald's church in Ashbourne.

Like St Francis, John was attracted while still young to the plight of the poor and adopted a life of humility and poverty, and until the day he died served the poor and the outcasts of the world.

Add to this that St Francis was also a poet and a dedicated intoner of psalms like John Bradburne. It was thus little wonder that John had great respect for and devotion to St Francis of Assisi, which lasted throughout his life time.

Jerusalem

Not knowing how he was going to survive and hardly caring, Christ's vagabond - for that is how he saw himself - made ready his frugal necessities for his epic pilgrimage, which he stuffed in a haversack.

Before he left, Dom Andrew Grey, whom John called his Carthusian guardian angel, gave him the name of a Franciscan monk in Jerusalem. When John reached Rome he was fortunate to find another Franciscan who told him that the monk he had been advised to contact was actually in Rome.

The new contact suggested to John that he should head for Naples with a view to journeying on to Jerusalem. All John had in the world was the Italian equivalent of £5 which had been given to him by a friend in Sussex.

He searched through his meagre possessions for something to sell and put up a pair of khaki shorts for auction in midst of the throng of pilgrims. A benevolent pilgrim paid far above the odds, giving John a tenner!

He now had £15, quite a sum way back in 1950, but hardly enough for a man bound for the Holy Land.

After Naples he visited Cyprus, Nazareth, Cana, Galilee and finally Jerusalem.

But before that goal was reached there were horrendous journeys on antiquated buses, ships and any form of transport he could cajole a ride on, and in between there was a lot of work for his feet to do. John never doubted that God would look after him. So he never worried, somehow the next meal always materialised, often a bed in a peasant's shack or joining fellow birds of passage for a bowl of stew at a monastery in return for a few jobs.

It was vagabondage of the most perilous kind at times, enduring all kinds of extreme weather and hardships. On one occasion he was put in jail accused on being a British spy.

Our Lady of Mount Sion

By pure chance (or was it the will of God?) while seeking the Benedictines on Mount Sion, he was wrongly directed to an order by the name of Our Lady of Mount Sion, which had been founded with the object of converting the Jews to Christianity.

Here, he enjoyed the hospitality of the monks in this delightful setting, refreshed himself after his journey and visited Mount Carmel to pray for guidance. John, once again, was advised to set off on his travels and head for the order's sister house of Louvain in Belgium.

Once more the God-seeking pilgrim was on his way, a bird of the air waiting for a favourable wind to guide his wings to a permanent haven where he could settle and devote his life to God.

The monastery was known as the House of Ratisbonne. Here he found joy and deep peace.

To quote his own words, 'I feel as if I've come to port after a long, stormy time at sea. Now my ship can be repaired and fitted well for more voyaging - I speak only in a spiritual sense of course. My vagabondage is done.'

An Abbot by necessity has to be a cross between a spiritual leader and psychologist. Being in charge of young men, postulants and novices in particular, he needs to have insight into the reasons why they wish to enter the secluded world of a monastery.

It is a life for a select, chosen few.

After a year John had itchy feet. The Superior General of the order was not surprised, suggesting in a letter to a Superior in Jerusalem, John's intended next port of call, that the young man was more suited to the life of Benedict Joseph Labre than a monastery.

Benedict, like John, was called to the religious life, and he tried without success to be accepted by an order - the Cistercians, Trappists, Carthusians - so he headed for Rome. So began an amazing pilgrimage of poverty - a holy tramp he visited monasteries all over Western Europe begging for food, suffering at the hands of brigands and being cast into prisons.

His goodness shone through, and even though he was virtually a silent man, he tended to the sick and consoled the poor and was compared to the legendary St Francis of Assisi.

In many ways John was similar to Benedict, a holy tramp of God.

Back on the road

Let John's poetry tell us something of his life once he had left Louvain:

I went through France when

all her corn was cut

and stood in golden sheaves:

I slept in barns, forestalled the dawn

ere swallows left their mellow eaves:

oddly or not I even slept

in ditches for God's paupers kept.

For the next year or so we find him on his travels. In Italy he walked up into the foothills of the Appenines to a town called Palma in Campania. He called on the priest who was delighted that John wanted to help him.

He put up a bed for him in the organ loft, which suited John - now he could play his favourite hymns, sing his psalms and pray the rosary in the solitude of his mountain fastness: the odd-job man fascinated the locals - an English loony, was John's idea of what they thought of him.

For several months this idyllic sojourn was the ideal tonic for God's wandering man of the highway. The out of the blue it was back to England. His father had died. Before leaving Italy, he made a vow of poverty and chastity to Our Lady. Like St Francis he wished to be wedded to the Queen of Heaven.

A wandering minstel I

His father's death brought John back to England. John's father had been puzzled at his son's conversion to the Catholic faith, but had eventually come to terms with it and the two had become reconciled.

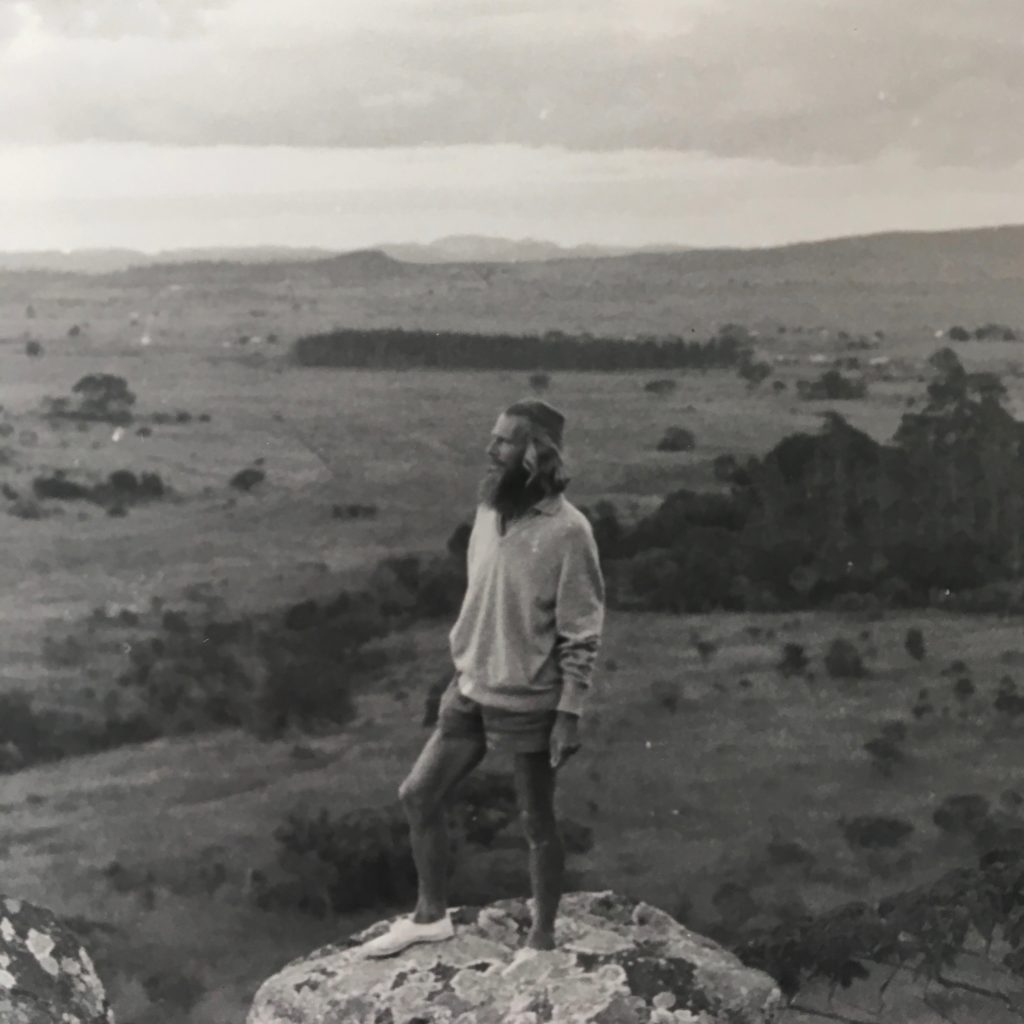

Back on his native soil, his longing for solitude was as keen as ever. He decided on a hermit's life and camped on the edge of Dartmoor, but even John needed the basics of life, and hearing about a shelter for homeless men at Ottery St Mary, he offered his services as a carer.

He soon became a familiar figure to the residents of the town, busking in the street, playing old English tunes on his recorder, gaily coloured ribbons dangling from the instrument; calling himself the jester of Christ, he donated the money he received to the parish church restoration fund.

'Buffoon for the Lord' was another title he delighted in: obviously well educated, an ex-army officers misfit, he was fodder for the newshound: one of them wrote: '... in this delightful backwater of tranquil England I discovered a charming, witty, well spoken young man, who, in a different setting, and a conventional suit of clothes, could have passed for an underwriter at Lloyds... he reminded me of a medieval minstrel singing his ditties 'neath the castle walls, amusing all who passed by with his jests and eccentric routine.'

If ever a man had itchy feet it was this strange nomad of God. The life of the cloister still appealed to him, but instead he had to settle for various jobs in Catholic institutions in and around London.

He often slept rough and displayed the minstrelsy he had begun in Ottery St Mary to people on the Embankment and other gathering places for the bizarre peripatetic visitors to the teeming metropolis.

I need a cave

Father John Dove S.J., who had served the army with John, knew his strange ways better than anyone.

Whatever John did came as no surprise to Father Dove. When he received a letter from his friend, enquiring if he knew of a vacant cave in Africa where he could live as a hermit, he knew that this was no joke.

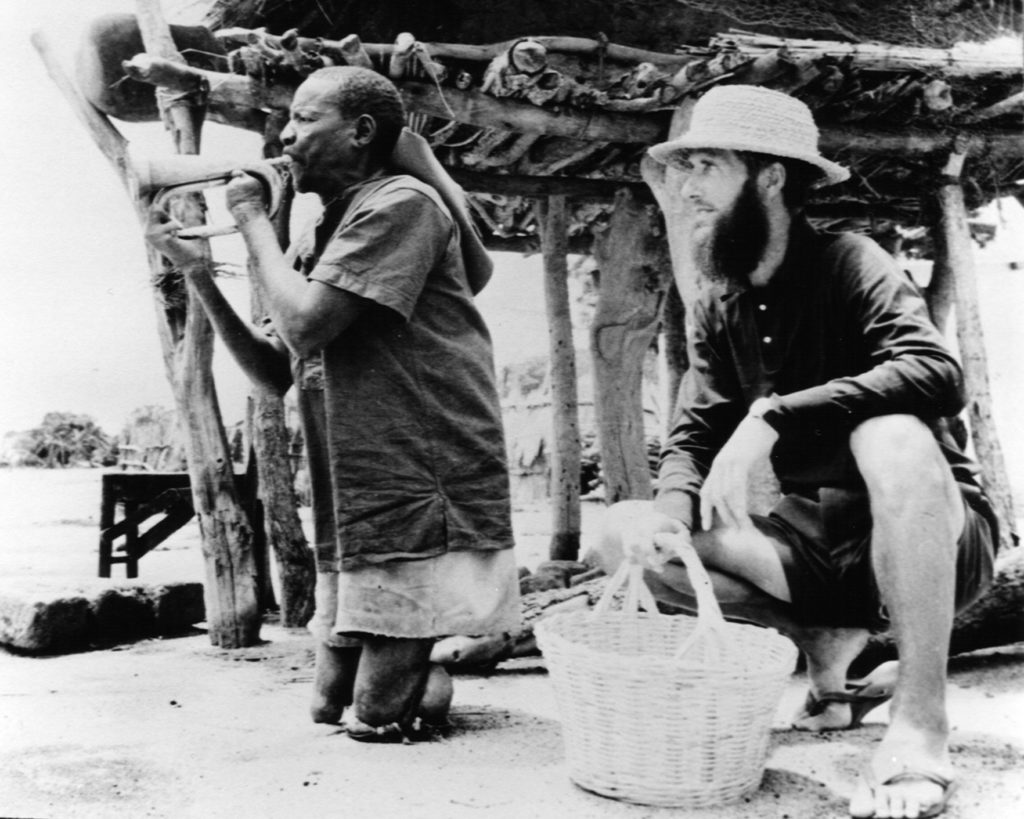

It was finally agreed that John should go to Africa and work in the missions as a lay helper. There were plenty of missions where he would be welcome.

John was not a practical person, and practical people were needed in religious houses.

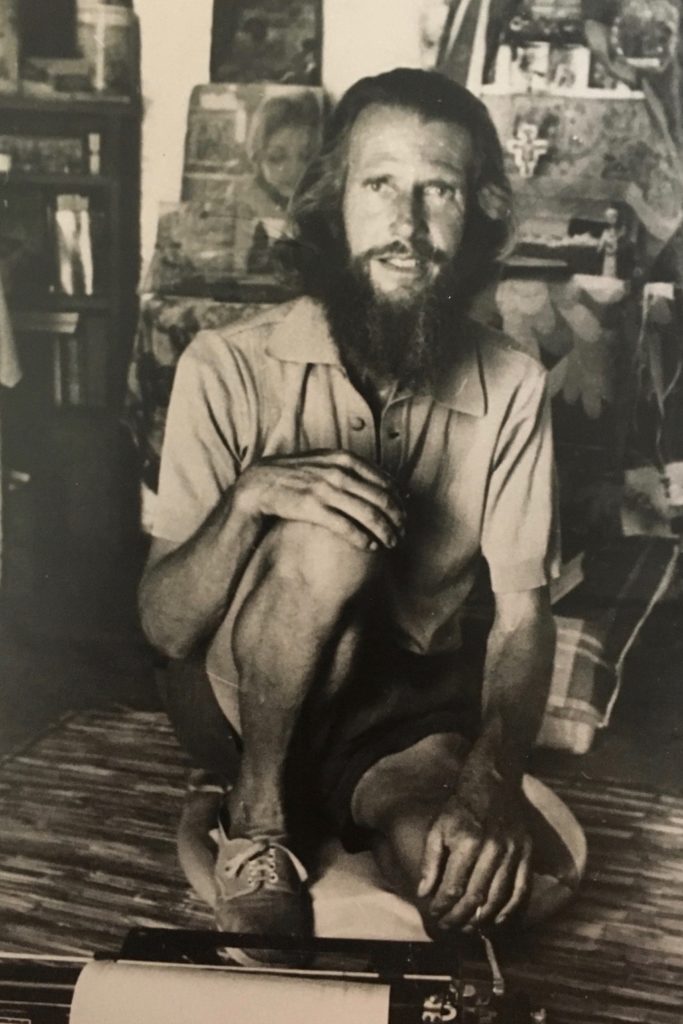

An odd-job man could be a boon; John was more suited to work in the gardens and farms where food was grown for the community and for distribution to the poor, but it was his great charity and compassion for the sick and aged that made him a celebrity of sorts - much to his great annoyance. He was embarrassed and longed to escape the curiosity of those who regarded him as a holy man; John was much happier as a nonentity doing jobs that white men never undertook.

To escape this unwanted attention he moved around living in isolated huts, tents and, for a spell, a hen house surrounded by clucking feathered fowl!

The miracle of the bees

It was in one of his primitive abodes that he took really drastic action. He wanted peace and quiet and couldn't get it. African bees are noted for being large and very ferocious. Your English garden bee is the soul of gentleness compared to its African counterpart.

Whilst John was staying at Silveira House, an education centre near Harare, John prayed to God to send a swarm to keep away visitors. Within a few days a whole colony had become residents of his hut. Wearing shorts and barefoot he sat among them playing his harmonium and writing poetry completely oblivious of their presence. It did the trick. Father Dove in his wonderful biography of John, Strange Vagabond of God, admits to being terrified of them despite John's assurance that they wouldn't sting him!

Since John's death many people have testified that after praying to John or being blessed by a relic they have been visited by bees.

John's three wishes

His first wish was to work with lepers.

His great hero Saint Francis of Assisi, in his desire to embrace poverty completely, realised that in order to attain this utter acceptance he must cast off all worldly trappings of comfort.

He gave away his belongings and dressed himself simply similar to the lepers who were cast out by their families to fend for themselves.

There is little doubt that John got his desire to help these rejects of society from the great saint and founder of the Franciscan Order.

John's second wish was to die a martyr and the third was to be buried in the habit of the Third Order of Saint Francis.

All three were granted, the third coming about in a most remarkable way.

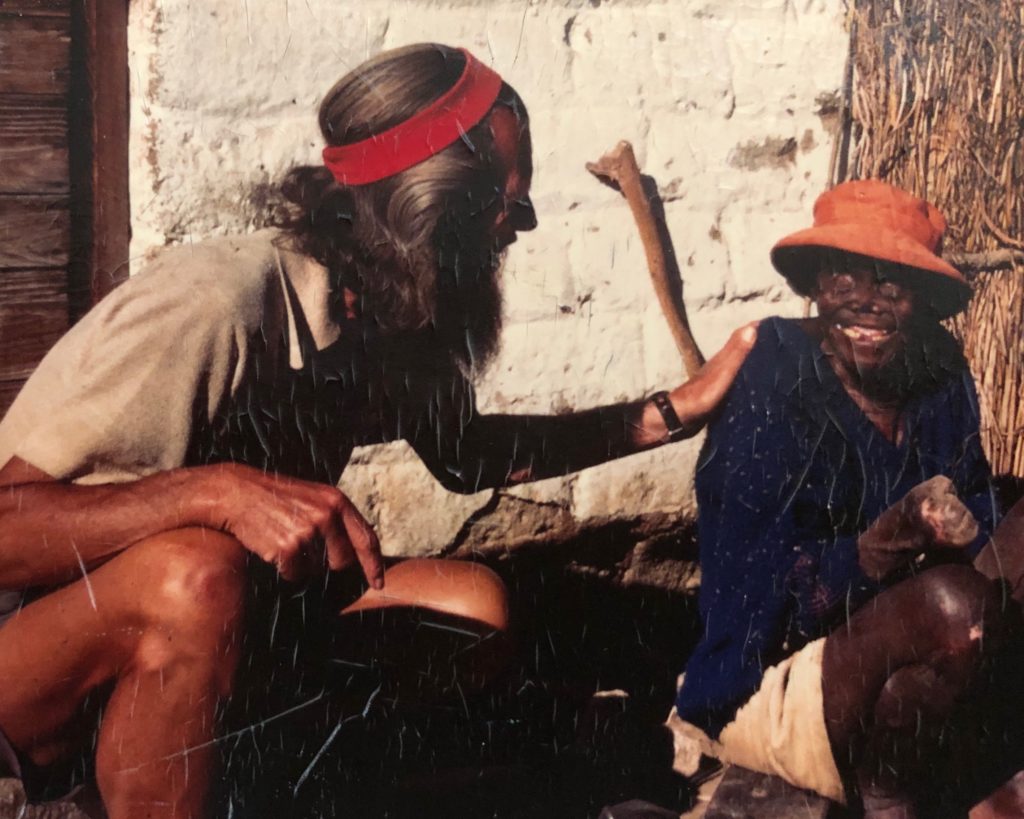

Mutemwa leper colony

It was almost by chance that John discovered Mutemwa. He had gone there with a friend from the missions, Heather Benoy.

Heather was amazed when John decided there and then to remain.

She told him he was mad but John was not to be dissuaded. She did persuade him to return to the mission for a few possessions before returning for good.

As soon as he saw the lepers he knew that God had finally found him his true vocation.

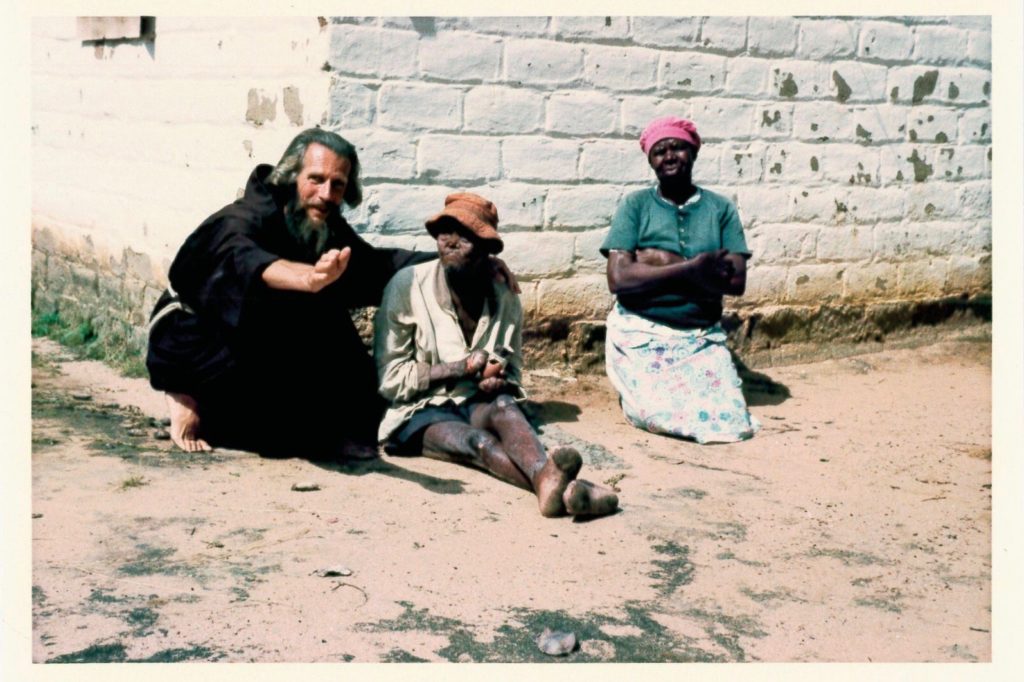

The state of the colony was appalling. It was nothing but a dumping ground for unwanted humanity. He was appointed warden by the committee. The improvements he made were nothing short of miraculous.

John treated each leper as an individual and a human being, washing them, feeding them and dressing their terrible sores.

In each of his charges he saw the face of Jesus, their bodies in ruin, faces eaten by this most dreadful of diseases.

Like Father Damien De Veuster in the previous century at Molokai, Hawaii, a notorious leper colony, John aimed to restore a sense of personal worth and dignity to the lepers.

He could even make them laugh - he got them singing to the accompaniment of his recorder and harmonium. Never before had these people received such care, such love, such fun!

They were his family and they loved him in return. John's apostolate lasted for 10 years.

Ups and downs

Before John's appointment the colony had been nothing better than a supervised prison.

Only the most basic needs of the lepers were attended to; John's subtle blend of gentle persuasion and charisma served him well, soon a doctor and a medically trained nun came to help him.

A chapel was constructed and John gave daily communion to the lepers.

His enthusiasm knew no bounds but his approach to the job angered some of the committee members.

He was told to reduce food rations, but he refused. He was told to put metal numbers around the necks of the inmates. He grew very angry, insisting that they were human beings, and not cattle. He was sacked and told to leave the colony.

Living rough was nothing new so he camped out on a large rock overlooking the colony.

The conditions reverted to the way they were before John's involvement. Sacked or not he ministered to them in any way he could, bringing in extra provisions and tending to their bodily needs at night.

He was accused of stealing provisions and other trumped up charges were brought against him by people he had upset with his blunt condemnations of injuries inflicted on his beloved lepers.

Some had long memories and waited for a chance of revenge, others secretly plotted his downfall. At all costs they would get rid of this interfering man.

War looms

The local inhabitants tried many ruses to get rid of John and the lepers. John would have had very little time for such folk!

He might have been a gentle, good humoured fellow, but he never pulled his punches when defending his principles.

The war in Zimbabwe was spreading and soon the colony became isolated, which resulted in necessary supplies becoming difficult to obtain.

Mystery still surrounds John's death but it would seem very likely that locals plotted to abduct him and to take him to the guerillas.

A story was invented about him being a spy for the security forces.

A group of people known as the Mujhibas, many of whom had crossed swords with John, abducted him at night on Sunday, September 2, 1979 and marched him at gun point to a guerrilla outpost.

John's good works had spread far and wide.

The guerrilla commander was an admirer of John's and told the Mujhibas that he had no argument with the good white man who had helped black people. Instead of shooting him, he asked John to look after the refugees. He refused and asked to be allowed to go back to the leper settlement.

Much to the anger of the Mujhibas, he was set free.

At dawn on September 5 they ambushed him, shooting him in the back, and left him by the side of the road.

After the shooting, three extraordinary events took place, when a small group of people tried to approach John's dead body. Firstly, they heard people singing, like a choir, but there was no-one in sight. They were very fearful, and ran off terrified. When they tried to approach again, they saw a huge white bird hovering over the body, as if to protect it. They ran off again, only to return later, and were overawed at the sight of three beams of light ascending from the proximity of where the body lay. The group finally ran off, and later a witness statement was made about what they had seen.

His body was found by a missionary priest and taken away for burial.

The magnificent eccentric was dead.

The three drops of blood

John Bradburne was devoted to the Trinity.

In honour of this devotion a friend placed three white flowers on the coffin to represent the Trinity - 'Three in one'.

During the Mass it was noticed that three drops of blood had fallen from the coffin forming a tiny pool.

Experts declared the blood fresh and bright, completely opposite to the blood of a dead man.

Upon the reopening if the coffin there was no sign of blood. The body had not bled. Onlookers were stunned. This was reported next day in the national papers.

There was no natural explanation. It did however ensure that John's wish to be buried in his Franciscan habit was fulfilled.

His body had been clothed in a shirt. A habit was obtained and John's body was robed in it and the coffin resealed.

The strange life-journey of John Randal Bradburne - poet, mystic, servant of unwanted people - had reached its end, a glorious finale.